Individual Excellence: Part II Process 5

29 June 2024

PART II: Process

Building a Framework of Processes

As mentioned above, it took me at least a year of working with the addictive population to realize that most people in early recovery are unable to accept (or believe) a compliment. A compliment carries a positive view or attribute of the complimented person. If you cannot believe good things about yourself, how will you build self-improving habits?

I facilitated SMART Recovery meetings for the addictive population for about twelve months before starting a second weekly SMART Recovery meeting for the Families + Friends of those suffering addiction. One of the most interesting differences between the protocols and literature of these meetings is the focus on self-care. Prior to doing this work, I would have guessed that those with addictive behaviours have a greater need of self-care than friends or family members. And I would have been wrong.

People in the F+F community also suffer from addictive tendencies. They mistakenly believe they can control much more than any individual has ever been able to control. Mostly, friends and family members believe they can control the lives of their addicted loved one. It seldom takes less than a year of thinking, doubting, and questioning before such people realize the truth of this fundamental reality, caught so well in the Stoic Serenity Prayer:

G-d, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change,

The courage to change the things I can

And the wisdom to know the difference.

That prayer is about metaphysics and epistemology. The metaphysics is about the intractably fundamental nature of life on Earth. As above, metaphysics consists of the study of being, including the limits of the universe, and the study of ultimate ends, or goals. If a person mistakenly believes he can control the thoughts, emotions, or behaviours of another person, the self-deceived controller spends his life in pursuit of the unattainable. This sounds like futility but, sadly, more people nurture this illusion than you may realize. The epistemology is in the third line, urging the praying person to know—to apprehend, challenge, discuss and test—that which is within human control and that which is beyond our control. It is for precisely such reasons, that philosophy should be taught from grade school onward in a truly civilized polity.

Despite the significance of that statement, I am starting with a corollary fact, not the principal truth. The principal truth becomes apparent when you are able to witness the effects of believing you can control another human being: your self-care goes on vacation as do many other health-sustaining habits you might have learned. You probably know someone like this. They are harried, frenetic, frightened, anxious and—paradoxically—out of control. They can no longer maintain commitments to self or others because of what their addicted loved one might (or might not) do today or tomorrow. That is, such people believe they are duty-bound to be available to their addicted loved one for as long as that addicted person is unwell.

The stunningly sad truth of this is that the longer the loved one continues to try to control the addicted person, the longer both will remain enmeshed in a downward spiral of mutual destruction. Sadder still, neither explicitly intends to harm the other but, as Ayn Rand, painstakingly documented, in her three principal works of fiction (We the Living, The Fountainhead, and Atlas Shrugged), it is altruism that corrodes, not selfishness when understood as an interest in one’s own well-being.

When the loved one begins to let go of the person with addiction, the addicted person has to begin facing the consequences of her own behaviours. I wrote has to which implies some sort of force compelling the person with addiction to do something different. That force is simple reality.

If I have no money for food because I spent what I had on my drug of choice, I look for someone else to provide that food. If I have a parent or sibling who is always willing to help, that’s where I go. But, if that parent or sibling realizes that they are 1) sacrificing their own wellbeing for me, and 2) enabling me to continue a long, slow death by suicide, things start to change.

First, the previously burnout loved one starts to take care of himself. As time moves forward, and his addicted loved one has accused him of every wicked selfishness known to humanity, he soldiers on with tears, the excruciating frustration of monstrous ingratitude, and, with a hop, skip, and a jump, increased personal health and resources.

Yet, none of this means that the loved one ceases loving or caring about his addicted friend or family member. What we counsel such people to say, to all the nasty accusations, is something like this: I love you and care about you so I’ll do what I can to support your recovery but not your addiction. That thinking and saying has consequences.

First, the blame is placed on the addictive behaviour, not the soul of the person suffering addiction. As the cliché goes, this is not a bad person, this is a person behaving badly for complex reasons. Secondly, the person suffering addiction hears about another way: recovery, for most people with addictive behaviours a dream long ago dismissed as impossible. Thirdly, the loved one has put realistic limits on their helpful capacity: I’ll do what I can. That does not mean I’ll spend the RESPs built over two decades for my children or that I’ll sacrifice my retirement savings. It means I will help you find a solution that works for both of us and anyone else willing to help.

Why have I taken two pages of your time to tell you this story—a story I’ve seen unfold too many times to count? I’m bringing this to your attention to emphasize and illustrate how difficult it is for people in our society to put their own self-care first. Within the F+F community, we too have lapses and relapses. Those involve forgetting or forfeiting our priorities in the interest of another for a short period of temporary reversal. In the same way that people with addiction have neural pathways reinforcing their need to kill the low (the beginning of withdrawal), so do we, in the F+F community have parallel neural circuits telling us we must control this life in need, even at the cost or our own health and security. This is the full madness of addiction within communities.

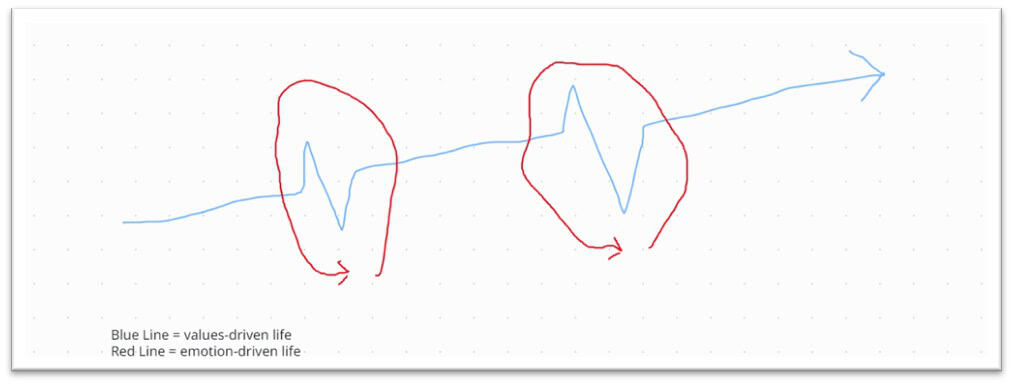

Succumbing to this madness precludes creating a set of healthful processes. It fosters what I call an emotion-driven life which looks something like the graph below, Figure 1.

Figure 1: Blue-line, Red-line

This diagram depends on a metaphor introduced earlier: life as a vector or arrow possessing force and direction. The blue line represents a values-driven life. Note that it is heading in a specific direction, and at a specific angle, but that is has breaks or interruptions in it—like any human life. Breaks, challenges, even tragedies are statistically normal parts of being alive for an average lifespan. Values-driven people stay on their blue lines, even when the agricultural hits the mechanical. Emotions-driven people, when the muck is flying, jump to the red circle surrounding a break in the blue line. This emotions-driven leap allows them to ruminate on a problem for as long as they wish. Some people in addiction call red-lining a pity party, some call it ruminating, I call it seductively unhealthy avoidance of the real issue.

The seductive power of the red circular line is that it offers a break in the hard work of building a life. It’s dead easy to whine, kvetch, and cry because life isn’t working out as you planned (Cf. Serenity Prayer, directly above). It is much harder, and requires discipline, to tell yourself that life has ups and downs and that downs offer a wonderful opportunity to test your self-control, courage, and resilience. As this book has attempted to emphasize, how you see the world is a choice you make every moment you are conscious i.e., each day from rising until bedtime we make choices, all the livelong day.

If you want to indulge your red line, you need read no further. If you want to increase the virtues necessary to stay on your blue line, you need some good processes.

To be continued next week.

Dan Chalykoff is a Registered Psychotherapist (Qualifying). He works at CMHA-Hamilton and Healing Pathways Counselling, Oakville, where his focus is clients with addiction, trauma, burnout, and major life changes. He writes to increase (and share) his own evolving understanding of ideas. Since 2017, he has facilitated two voluntary weekly group meetings of SMART Recovery. Please email him (danchalykoff@hotmail.com) to be added to or removed from the bcc’d emailing list.

Comments