Stoic Values VIII

11 November 2023

Coming to terms with the death of a loved one is not something most people see as harmonious with the ebb and flow of daily life. We perceive the deaths of loved ones as tragic major milestones on our own lifelines. The Stoics are behind many of the ideas in 12-step culture, and in modern psychology, where Rational Emotive Behavioural Therapy morphed into Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, both of which are used extensively in treating addiction. Yet last week this blog discussed the challenges of accepting the Stoic valuation—of life itself—within the category of preferred indifferents.

Turning to Heraclitus, my favourite pre-Socratic philosopher, what do I find in relation to this issue? “There is one wisdom, to understand the intelligent will by which all things are governed through all” (Patrick, 2013, p. 48, Heraclitus’ Fragment XIX). In the seven blogs preceding this one, I have argued that evidence-based thinking provides more support for chance than an intelligent will being the random governor of all. What is much less governed by chance is focused human activity which is governed by reason-driven order (more on this, below).

The quoted fragment, from Heraclitus, is in general agreement with Stoic metaphysics which perceived and described the universe as “…coextensive with the will of Zeus, the impersonal god. Consequently, all events that occur within the universe fit within a coherent, well-structured scheme that is providential” (Stephens, 2023, 1. Definition of the End). If that providential premise is accepted, the death of a loved one has unfolded naturally or, as Epictetus put it, “Never say about anything, I have lost it, but say I have restored it” (Long, 1991. Epictetus, Enchiridion, XI). If, however, you maintain that the universe is governed by chance, your sentiment might well be that I have lost it, and it cannot be restored. The interesting similarity, between these two takes on creation, is that both find the mourner alive with life ahead, and the deceased relegated to time past within living memory. So what is the right = virtuous thing to do when death is upon us?

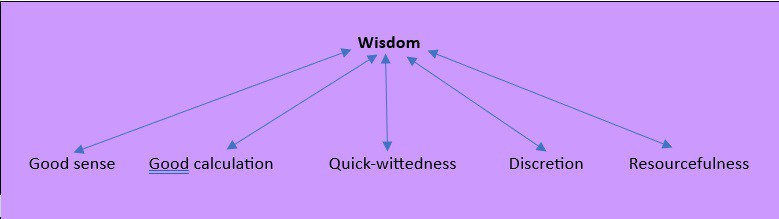

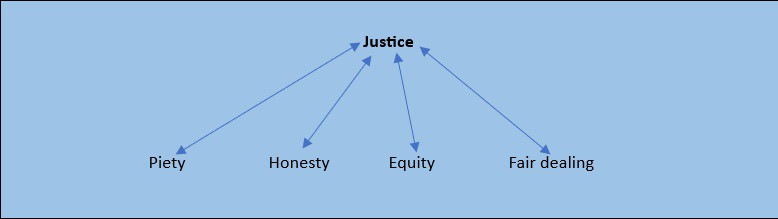

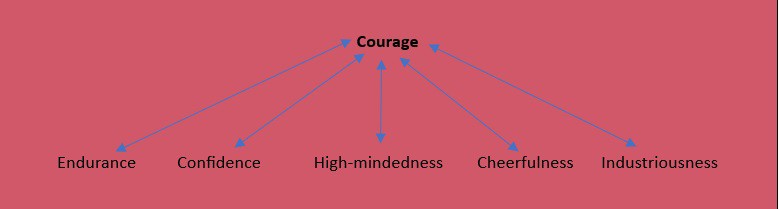

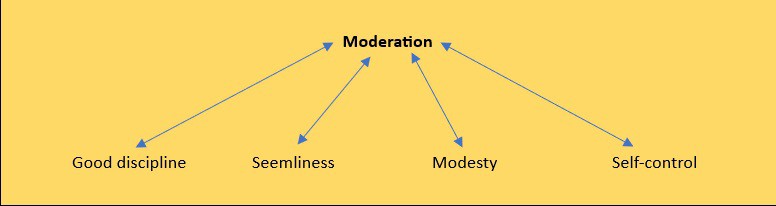

The Stoics devised a lovely hierarchy of virtues with four primary values: wisdom, justice, courage, and moderation, illustrated in the four rectangles, below.

Which of these virtues serves a chance-and-evidence-based thinker best? From wisdom, the bereaved could profitably draw upon good calculation and resourcefulness. Good calculation provides an estimate of statistical life probability of the bereaved as well as a reckoning of available resources, which might include loved ones, family, earning potential, as well as long- and short-term goals. Resourcefulness would then allow that person to make prudent use of those assets while also calling upon social and personal supports like, again, family and friends, but also professionals, and voluntary groups for the recently bereaved. Grief counselling, resilience, exercise, getting out into the community are also part of resourcefulness, as are favourite paintings, books, movies, sports, places, and music.

Justice, at first glance, seems less relevant but on deeper reflection is critical to a balanced mind. For example, if our bereaved friend sees the loss of his loved one as unjust, he may never be able to fully accept that loss as an unfortunately predictable part of a chance-based (or deity-based) life. If another bereaved friend felt that a deity had removed her loved one from our Earthly realm, she might wonder, Why my loved one? Why so early? as I have often wondered at the death of Denise Dewar, my fifteen-year-old cousin who died in 1970.

Denise was born with cystic fibrosis preventing her from breathing successfully to such an extent that she often had to sleep in an oxygen tent or be hospitalized. So how can the Stoic virtues help? If piety is defined as unthinking reverence, it is less useful to evidence-based humans. If, however, piety is understood as reverence for beauty or life, I have had decades to revere so much love, architecture, space, art, music…values that have brought continual and renewable solace. I feel that in honouring equity, another facet of Stoic justice, Denise’s absence has helped me see what a privilege my time has been.

Honesty is important. In 1970, Cystic-Fibrosis.com informs me, the life expectancy of a person suffering that disease was in late teens—kind of shockingly, Denise did statistically better than I knew. And this is important. If you buy into the premise that eudaimonia (well-spiritedness) is the ultimate destination in life, then you are already in the same neighbourhood as Aristotle (Nicomachean Ethics, et al.) and the Stoics, (per Stephens, herein). In that neighbourhood, rationality is what makes you human. Use it. I wish I had used it more during the years I spent time with Denise. But I was a kid and I hoped, prayed, and denied statistical reality knowing, from the family, that Denise wasn’t expected “…to make old bones,” as our Nanny used to put it.

Where justice grates is in the idea of fair dealing. Who dealt the card that said it was fair that I got six-plus decades while Denise got fewer than a couple? I know I have thought that way and I also know it’s fallacious thinking because it assumes the Fates, or another card dealer, exists in the sky. These are factors far, far from our control so my responsibility is not for Denise’s short life but for loving her as best I could and taking the maximum advantage of the resources at my disposal i.e., moving meaningfully toward self-actualization.

What seems most interesting—and surprising—about Stoic courage is that cheerfulness is included. Again, once that’s reflected on, it makes good sense. After all, cheerfulness is no more than an optimistic attitude toward one’s peers and one’s pursuits—and, based on my experience, it takes considerably less courage to be pessimistic than optimistic. And this happens for at least two reasons.

First, we are adaptively evolved to be more pessimistic than optimistic, as it keeps us safe. If you’re a cavewoman, and you know the smell of tigers, you’re at an adaptive advantage if you stay clear of that smell and that creature. Given that advantage, we are maybe maladapted toward optimism today but at least we know why. Secondly, it seems embarrassing to dream big and achieve small. Knowing the sting of humiliation, those of us with less confidence tend to understate our goals and expectations to avoid future disappointment. I suspect that avoidance detracts from the energy required to accomplish goals.

In terms of virtues that help deal with death, courage has a lot to offer. Endurance of the hardship and sadness; confidence that better days are coming, cheerfulness, as above, and industriousness keeping us well occupied, while grieving occurs, are all useful.

Moderation may actually be king of the big virtues in the loss of loved ones. If we understand seemliness as contextually appropriate behaviour (a bit of British stiff upper lip stuff) seemliness works remarkably well with discipline, self-control, and modesty. Both research (Twenge, 2009 pp. 1-9, et al.) and day-to-day life tell me these virtues are not fashionable in our woke age but that cannot last for long. While, as a psychotherapist, I am well aware of the holistic need to experience our emotions, I have yet to read research telling me that emoting loudly and rudely in public has any selective advantages at all.

If we return to our morbid, but all too real visitation with death, it is easy to see that the sub-virtues of moderation allow you to go about your professional and social life, even while in serious emotional pain, saving the necessary crying and heartache for more private places and company. It is in the practice of these virtues that the more vernacular and scholarly understandings of Stoicism collide.

In the second paragraph of this blog, you were promised a return to the premise that human activity is governed by reason-driven order. That statement relies on the implicit assumption that nature is chaotic and disordered, and that the universe is nature writ large. When we look at the effects of high rain and wind on a city, we see the chaotic, random destruction that nature brings to our designed, built, and evolving contexts. As many urban thinkers have taught me, cities are probably our noblest artifacts based on engineering, architecture, and voluntary social activity.

When we look at death, we also experience the chaotic, random destruction that nature brings to our designed and evolving lives. Rational acceptance of the death of loved ones, per this blog, is a multi-faceted program. Cities and individual lives require significant organizational energy and maintenance. None of that energy is easy to summon, hire, or deploy. However, this is the value and offer of philosophy: embrace the disciplined use of empirically validated tools of thought, emotion, and behaviour or succumb to the random ebb and flow of chance.

Dan Chalykoff is a Registered Psychotherapist (Qualifying). He works at CMHA-Hamilton and Healing Pathways Counselling, Oakville, where his focus is clients with addiction, trauma, burnout, and major life changes. He writes these blogs to increase (and share) his own evolving understanding of ideas. Since 2017, he has facilitated two voluntary weekly group meetings of SMART Recovery. Please email him (danchalykoff@hotmail.com) to be added to or removed from the Bcc’d emailing list.

References

Long, G. (Tr.). (1991). Epictetus’ Enchiridion. Prometheus Books.

Patrick, G. T. W. (Tr.) (2013). The Fragments of Heraclitus. Digireads.com.

Stephens, W. O. (2023, September 1). Stoic Ethics. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://iep.utm.edu/stoiceth/#:~:text=All%20other%20things%20were%20judged,be%20used%20well%20and%20badly.

Twenge, J. M. (2009). The Narcissism Epidemic: Living in the Age of Entitlement, Free Press.

What an excellent read, Dan! Much appreciated!

Thank you, Trish.

Thank you Dan for such an insightful and inspiring post.

I shall try to learn from this when feeling grief that can at times seem so overwhelming.

We’re all trying to learn, Nancy. Thanks for reading.