Maslow’s Love & Belonging Needs

9 June 2021

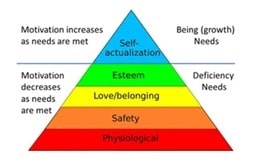

Two things we can take from this exploration of Maslow’s hierarchy so far: 1) Gratitude for and regular acknowledgement of our physiological needs makes us more fully aware and present—humans being; and, 2) The unmeasurable nature of our safety needs is only considered when they are absent.

The third band from the bottom of the Maslovian pyramid is Love and Belongingness: acceptance, friendship, intimacy, and relationships. Here’s the graphic to keep it fresh.

Figure 1: Abbreviated Maslovian Hierarchy of Needs.

This is where the factors from physiological and safety needs pay off or fail. For example, to be able to initiate and nurture friendships is a skill requiring pretty sharp social sensitivity. Is the other person enjoying this chat or trying to get away? Am I pushing too hard, too fast, or is this about right? Do I have to enjoy all her jokes, or can I ask her when I don’t get it? Will Mary be angry with me because they were friends first? And on it goes.

But...if the person who has initiated the friendship is rejected, her upbringing and home culture will make ALL the difference. Let’s look at two people with different home cultures.

Dick has two parents who are gratefully married and happy to have their children, Dick and Tracy, in their lives. They are not perfect parents, but they are usually available to their children and typically willing to discuss and explain if things don’t seem right to either Dick or Tracy. Both parents are reasonably competent in their emotional intelligence and thus in social skills, so they enjoy an extended family and a broad set of friendships. Both parents work, one fulltime, one only when the kids are in school. As you can probably see, this family has been fortunate and smart in meeting Maslow’s physiological and safety needs: air, food, drink, sleep, warmth, exercise; and, security, stability, health, shelter, money, and employment, respectively.

Jane has a single mother and three younger siblings. She has never met her father but has heard many bad things about him. Her mother is always rushed, frequently angry, often sad, and her speech is slurred from the consumption of rye-and-coke by eight o’clock most nights. Many nights Jane has stayed awake so she can extinguish her mother’s lit cigarette when her mother passes out. Jane then tidies the kitchen, turns out the lights, and goes back to bed.

If Dick befriends a new guy at school and gets shot down, he has the sense that there’s something wrong with this new guy because Dick knows he wasn’t rude, pushy, or mean. If Jane gets shot down, after weeks of working up the courage to talk to a potential friend, Jane has the sense that she messed that up completely. How could Jane be so stupid? How could she have handled that so badly? What a loser I am, thinks Jane.

I’m sure the picture is clear. The point of the examples is to demonstrate the relationship between formative and performative factors in the physiological, safety, and love & belongingness stages of Maslow’s hierarchy. Jane does not feel she belongs anywhere. As the oldest child, she is responsible for her siblings, takes responsibility for her parent, and receives almost no affirmative appreciation for her skills. Similarly, Jane is far too preoccupied with life safety issues to have developed a rich emotional life in which her feelings are recognized and respected within her family. In fact, the constant panics induced by her mother’s behaviour leaves Jane thinking she has NO time for feelings and has already put her adrenal glands in overdrive. Stress bordering on trauma; tobacco, alcohol, and dysfunctionality are some of the physiological and (un)safety factors Jane inherits.

The saddest part of Jane’s unmet needs, for love and a sense of belonging, is not any shortage of social acceptance, it’s that Jane doesn’t accept herself as good enough. Despite the fact that she has, when situations have demanded it, taken responsibility for four other human beings (by the time she is twelve years old), made her way through school plagued with depressive anxiety, and has a plan for getting out—she’s still a loser. Why? Because she’s measuring herself by a set of untested extrinsic standards.

Jane has uncritically (i.e., without testing or challenging them) believed that most of her classmates come from homes with nice green grass, white picket fences, and two perfect loving parents—dreamland. No one comes from such a place. No one. If Jane tested the standards she has adopted, some of her questions would be: What did those people do in emergencies? What did I do when my mom passed out with a lit cigarette in her hand as she fell out of her chair and onto a carpeted floor? What does that say about me? What does that say about me in relation to others? If such questions keep being asked and answered accurately, Jane’s standards—the criteria she uses to measure her own value as a person—will move from extrinsic (crated by others) to intrinsic (coming from within).

What’s interesting about this, with respect to Maslow’s hierarchy, is that one could argue such a move, from extrinsic to intrinsic standard-setting, is a cognitive or self-actualizing need, respectively two and four ranks above love and belongingness needs. And yet Jane, like many others, has moved from such a position of deficiency—imperfectly and partially—to a position of growth.

Dan Chalykoff is working toward an M.Ed. in Counselling Psychology and accreditation in Professional Addiction Studies. He writes these blogs to increase (and share) his own understandings of ideas. Since 2017, he has facilitated two voluntary weekly group meetings of SMART Recovery.

Comments