Exiting the Stages of Change

8 September 2021

People in recovery sometimes think about exiting the stages of change hoping to move from great to gone. In SMART Recovery, some are in those stages while others are in a not-so-good to alright stages. Believe me, please, when I say it’s not where you’re at that’s important; it’s movement itself, in the direction of healthy order, that makes each day worthwhile.

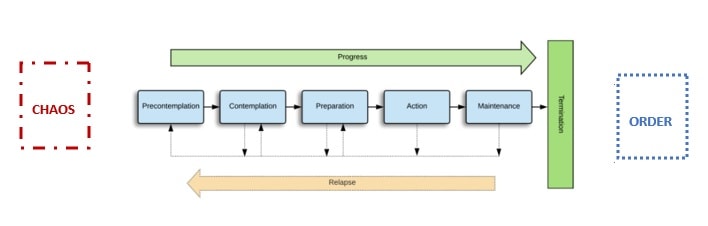

At a recent meeting, the stage labelled “termination” in Fig. 1 (vertical green box) was discussed. People wanted to know if one actually exits the Cycle of Change (CoC). We’re going to look at this in a couple of ways.

First, let’s look at what Jeremy Sutton (chart above) said in his article on the CoC. The summation, of the termination stage, is “I am changed forever” which is elaborated as a place in which the desire for a return to old ways is absent. No goals are required as the client has absorbed behavioural change with no temptations and self-efficacy of 100%. Mr. Sutton does provide a caveat at the bottom of his description stating that alternative views exist claiming that termination is never reached. I’m afraid I’m one of those alternative voices. Here’s why.

Last week we used Bandura’s (1997, p. 3) definition of self-efficacy as “...belief in one’s capabilities to organize and execute the courses of action required to produce given attainments.” A 100% self-efficacy rating seems a proclamation of hubris, that ancient Greek condition in which excessive pride provokes the Fates into bitch-slapping you with a major hit of humility.

Maybe it’s my age, maybe it’s my life story, or maybe I’m just an anxious guy, but I don’t do anything without resorting to Seneca’s premeditatio malorum (precontemplation of evils). Bad stuff happens. Every day. That doesn’t mean you should wallow in dread or fear for hurricanes before heading out to get your groceries. But it does mean that we lose loved ones, grow cancerous tumours, and have bad turns of fortune more often than we’d like.

I remember my father making an excellent point the day I returned home from high school with a list of Machiavelli’s claims. The claim my father responded to was that a man remembers the loss of his fortune longer and more painfully than the death of his father. Though my grandfather was still alive, my father said, “That’s not a fair claim. I expect my father to die but I don’t expect to lose everything I own.” And he had inadvertently made Seneca’s point for him.

Seneca warned that it is the unexpected blows that mess with our serenity. To preclude that mess, Seneca taught himself to contemplate as many bad news events as he could, as a regular daily practice. Many people will be repelled by this and argue that it just makes you miserable thinking about all this bad stuff. The Stoic response might be, “I contemplate misfortunes so I can roll with the punches and maintain my composure or sophrosyne.” The latter word is defined as “Moderation or temperance...this word stands for the quality of quiet and discreet people who do not make disturbances” (Sparshott, 1996, p. 442). Significantly, it’s oft-cited antonym is hubris.

That’s the first point. Exiting the CoC seems to me an act of hubris or excessive pride—it’s tempting the Fates, G-d, or the reward circuit in your brain, whichever shivers your timbers. It seems to me wildly immoderate to expect 100% of anything from yourself or another. The nature of life simply contains a constant measure of uncertainty, at least in my estimation and experience.

The second reason a full exit from the CoC is difficult to support concerns the definition of addiction. Addiction requires a susceptible organism (a person), a drug with addictive capacity, and stress. As I understand this, the susceptible organism and the stress easily trump the addictive drug in their impact on addictive behaviours.

As covered in the blog on Love & Addiction (18.viii.21), our attachment style is determined in infancy. At that point, our susceptibility to addiction, neediness, and low self-esteem is set. While that set point is not immoveable, it is established to such an extent that it will affect one’s personality for the duration of her—e.g., Audrey’s—life. This means Audrey, our susceptible organism, has a higher tendency to behave addictively.

It also means Audrey is less resilient when faced with stressors. She has been clean and living a well-spirited life for four years. After four years, Audrey feels a bit of been-there-done-that about both her 12-Step and SMART Recovery meetings, so she stops attending at first gradually and then all-together. She feels she has exited the CoC. Nothing falls apart, her life keeps moving forward as she’s hoped it would. And then she finds out her lover has been cheating on her. For over a year. And then her on-again-off-again mother dies—the next week.

Audrey is feeling utterly beaten down, alone, and vulnerable to these two major stressors. The neediness, aloneness, and low-self esteem are working overtime through her negative self-talk. Either of these two stressors is serious enough to derail (at least temporarily) the most resilient of people but the two together are almost overwhelming. Without even realizing it, Audrey, while out walking at 8:00 one night, finds herself back on the street where she used to score. Like five years ago. And guess what, in ten minutes she’s snorted two lines and is heading to the bar for shots.

What am I saying? I’m saying that if Audrey knows she had attachment issues, dysfunctionality, addiction, or trauma in her upbringing, then she knows her ability to deal with stress, addiction...will require a sense of quiet, dignified humility aiming at what the Greeks called sophrosyne, defined above.

Audrey’s story will not unfold the same way for all who exit the CoC. But the smart money is on sticking with your program and thinking about your place in the CoC for the rest of your days. That doesn’t mean enduring dull routine, it means creative effort and renewed perspectives are required. And that behaviour will make it much more likely that your remaining days are in healthy recovery.

Dan Chalykoff is working toward an M.Ed. in Counselling Psychology and accreditation in Professional Addiction Studies. He writes these blogs to increase (and share) his own evolving understandings of ideas. Since 2017, he has facilitated two voluntary weekly group meetings of SMART Recovery.

Comments