Maslow’s Safety Needs

2 June 2021

We resume our exploration of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs at the second from bottom band of his pyramid. (Last week’s blog looked at the bottom band: physiological needs.) This level is categorized as safety needs. Those include security, stability, health, shelter, money, and employment. As some of you may already have gleaned, these needs (safety) are impossible to quantify. How does one know when she is secure? Is it an emotional condition or an objective set of physical and physiological requirements? And before we go further, I should add that Maslow’s theory is something of an enigma itself.

That enigmatic quality arises from the fact that replication of the truth and order of his stages has been mixed. And in some ways, this is as interesting as the theory itself. Like Freud’s or Erikson’s theories of development, all of these continue to appear in textbooks of psychology. If they cannot be shown to be true, why are students of psychology still required to learn these theories?

The apolitical answer is that they remain because they are part of the history of the discipline. The more controversial answer is that they contain truths that do not lend themselves to replication of results through the methods used by hard science. Which is why it’s interesting.

Epistemology is the division of philosophy that looks at what we know and how we know it. You don’t perform open heart surgery or fly astronauts to the moon based on non-verifiable theory. Or do you? I can recall conversations with a surgeon-uncle who told me the human body is every bit as unpredictable to a surgeon as an old building is to a restoration contractor. The basics must be there, but not necessarily where you expect to find them. If this is true, and in the architectural instance, I know it is, we use statistics all the time to bet on the probability of success.

Returning to Maslow, I believe his hierarchy is still taught because it contains truths many of us experience at a qualitative level as our lives are lived. Further, I will hypothesize that his theory has consistently offered one of the qualities required of good science: explanatory validity. His hierarchy continues to allow us to explain the lives of some of our fellow human beings in ways that would not be as otherwise satisfying.

Given the unquantifiable nature of security, stability, health, shelter, money, and employment, how do we know when we have achieved these values? I want to say that we know we’ve achieved them when we start to pursue the values on the next tranche of Maslow’s pyramid but—I’m not buyin’ it.

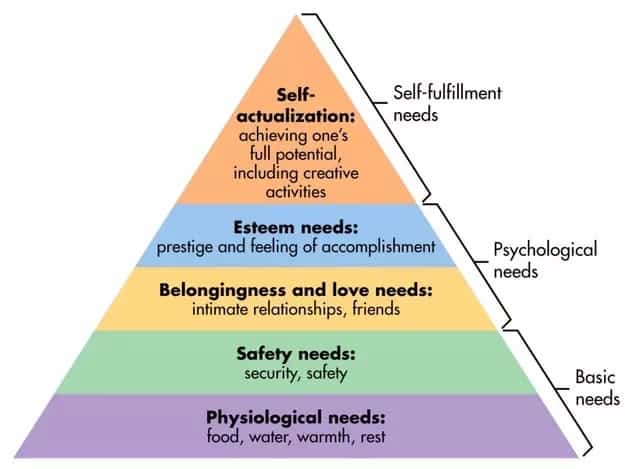

To be clear, I’m not rejecting the hierarchy, I’m rejecting the condition that one set of needs must be fully satisfied to move to the next. Why? Because human life isn’t that neat and tidy or that consistent. I believe people can seek purpose, aesthetic delight, or understanding long before they have a mortgaged house and yard. That house and yard fall under deficiency needs (bottom half of pyramid) while aesthetic ambition, purpose, and understanding fall under growth needs (top half, Figure 1).

Figure 1: Abbreviated Hierarchy of Needs per Maslow

What I do agree with is that without having all the deficiency needs met, those personalities are visibly troubled and troublesome. And I believe there is a reason Maslow thought so hierarchically and mechanistically about these ordered conditions.

Evidently, Maslow didn’t come into his own (an interesting phrase) until he was working under Alfred Adler. Adler had been one of the original acolytes under the mighty Sigmund Freud. Adler was also the first of the acolytes to abandon ship, claiming that psychology ought recognize social needs as well as psychosexual needs. But Freud, Adler, and Maslow were all products of a positivistic zeitgeist (spirit of the time) that insisted on definitive relationships, not just sets of probable outlines or correlations. And while I want the person who repairs my car to be certain the brakes are working to spec, I don’t expect that mechanic to know the driving conditions, recklessness, or other imponderables my car and I will meet in the next few months. That is, sometimes life unfolds per well-observed theory; often it unfolds with glorious unpredictability.

So how do we know when our safety needs are met? I believe these needs assert changing influence on each of our lives. As our values become more outward looking, broader, less about us, our safety needs recede. In more basic terms, a woman whose life is focused chiefly on cutting edge astronomy, family, and health, probably doesn’t award much of her time to stability, health, shelter, money, and employment because she has these in sufficient abundance to allow her to forget them in favour of the pursuit of her higher values. In short, we’ve probably met our safety needs when we realize we’re not thinking about them!

Dan Chalykoff is working toward an M.Ed. in Counselling Psychology and accreditation in Professional Addiction Studies. He writes these blogs to increase (and share) his own understandings of ideas. Since 2017, he has facilitated two voluntary weekly group meetings of SMART Recovery.

Comments