Wokusts, Big Bangs, & Windhovers: The Need for Faith, Ritual, & Reverence

26 October 2024

The section of the manuscript from which I’m working, is entitled Processes, which began with a quote about religion. I have never been able to practice a religion though I’ve only really tasted two, Christianity and Judaism. With its frequent calls to sacrifice and placing others above self, Christianity has never worked for me. I find it hard to sit still and not to counter the arguments of Christian clerics—but courtesy dictates that a church is not the forum for debating ideas. Which is, in itself, interesting.

The second, Judaism, is very near to my heart because some of its practices, and most of its culture, had me feeling at home from the moment I began introductory courses. My respect for Israel and for what the Jewish people have built—and defended—knows no current rivals. I tell you all this, so you know my honest position within the realm of organized religion: nowhere.

And that’s a problem, per the thought with which we began this section of Processes, Faith, Ritual, and Reverence. “Out of seven billion people in the world, six billion think religion helps them live a long, meaningful life--and science tells us they're onto something” (Pinker, 2014, p. 73). I suspect that what those people have, that I don’t, is faith, ritual, and reverence at a more fundamental level than me and many other non-religious Westerners.

I’m also not sure that what I’m seeing in world events isn’t reflective of that schism: woke thought and radical Islam versus a spiritually wobbly West. We will look at three approaches to the vital problem of faith, ritual, and reverence.

Epistemology of Woke Dogmatism versus Classical Liberal Freedom

- A Wokust judges.

- A classical liberal considers.

- A Wokust looks first at your skin colour, second, your socio-economic past, third your collective adverse history based on equality of outcome.

- A classical liberal assesses character in light of individual histories based on principles of equality before the law.

- A Wokust allows for no null hypotheses i.e., If you are white and claim you are not privileged, you are a lying racist. If you are white, and admit your privilege, you are racist i.e., there is no way for a white person to be fair-minded. A Wokust judges based on chromatic class. This violates broadly accepted standards for the identification of facts.

- A classical liberal assesses individuals based on behaviour and testimony with the very real possibility that any person—of any colour—might or might not be racist.

- A Wokust uses any form of coercion possible to cancel or silence voices that threaten the legitimacy of their incredibly fragile metaphysics of increasingly restricted thought.

- A classical liberal invites someone with an opposing view to debate those ideas in an open forum so that all comers can benefit from open discussion of free thought.

If you can affirm any of the premises numbered “1,” you are wasting your time reading any further. If you are actively wondering about, or affirming those premises numbered, “2,” please read on. Here’s the relationship between these dichotomies and faith, ritual, and reverence. If you base your faith, rituals, and reverence on a creed that intentionally excludes any prejudged portion of humanity from voluntary involvement in your reverence, you have defeated the spirit of the endeavour. The endeavour of faith, ritual, and reverence, at its heart, is about our sameness, our aloneness, our wondering, and the magnificence of the opportunity of life.

Hawking’s Take

If a person considers herself an essentially rational creature, per Aristotle’s differentia, she pays attention to high levels of rationality. As such, I have always been curious about the metaphysical views of top scientists. Recently, one of Stephen Hawking’s later works made its way to my sphere of attention.

The question he was answering was Is there a G-d? Working backward from his conclusion, I will try to render the essence of his argument. Hawking’s answer is that, no, there could not be a G-d (understood as the supreme first cause) because the big bang that created the universe also created time i.e., time didn’t exist prior to the universe so there was no time for anything or anyone to exist, let alone time to create something so large and complex that it is nearly incomprehensible. Hawking went further, arguing that neither does the universe have a cause as there was no time for a cause to exist.

Even writing those sentences sends chills up my spine. The sense of aloneness in the universe is staggering and yet, here we are. Not only have we created periods of peaceful, enormously cooperative productivity, but we have, just in the last century, travelled successfully into space, transplanted human hearts, and moved the measurable standard of living of most Westerners to previously never-known heights.

As you would expect, Hawking arrived at his position with impeccable logic. Here’s my synopsis of his argument:

- A universe requires matter (mass), energy, and space.

- Energy requires negative capability (the hole created by digging soil to build a hill).

- Positive and negative energy always sum at zero i.e., the energy required to dig the hole is equal to the energy required to build the hill.

- The Big Bang, in creating wild positive energy, necessarily created a precisely equal sum of negative energy that is contained in space. Think gravity and think of what’s keeping nearly an infinity of galaxies in balance.

- If you accept Einstein’s E = mc2 you cannot refute the above. That’s because mass (m), at a certain velocity (the speed of light, c), becomes kinetic (moving) energy, (E) (Hawking, 2018, pp. 31-52).

So…we are left with no G-d as there is simply no place for G-d in a universe with the creative explanation offered above. And here’s where the parts come together.

If you choose to walk away from those five points, your faith, rather than your reason, is dominating your epistemology. Emotionally, I don’t like this either. Every time I write a clause like “there is no place for G-d” I feel a sense of ungrateful betrayal. I need G-d as someone/something to whom I can offer thanks. This is how I feel.

But, I’m also a psychotherapist. And some of the most convincing arguments recently made in psychology e.g., attachment theory, go a long way to explaining such a need. We are complex, evolving creatures whose fate alone in nature trended very poorly indeed. (Think Hobbes, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short!) For a man, a child, a mother to imagine they are totally alone and totally unguided in this world of perils can be unquestionably frightening. I get it. But we also owe it to ourselves—if we choose to live Socrate’s examined life, the only one worth living—to have a responsible system of epistemic accounting i.e., what do you know, and how do you know it? Hawking’s argument is simple in essence and complex as hell in detail, but I would not take the opposite side in debate as reason was his raison d’être.

Further, the existential call we each seem to possess—for meaning—feels completely defied by Hawking’s explanation. Where is the meaning in being abandoned in some godforsaken corner of a nearly infinitely large universe? Well, that’s why we need philosophy, faith, ritual, and reverence, in that order—to understand what our individual and community-based lives mean. And that is where I believe the West is failing itself. More succinctly, dogma must fall, philosophy, faith, ritual, and reverence—for Earthlings—must rise.

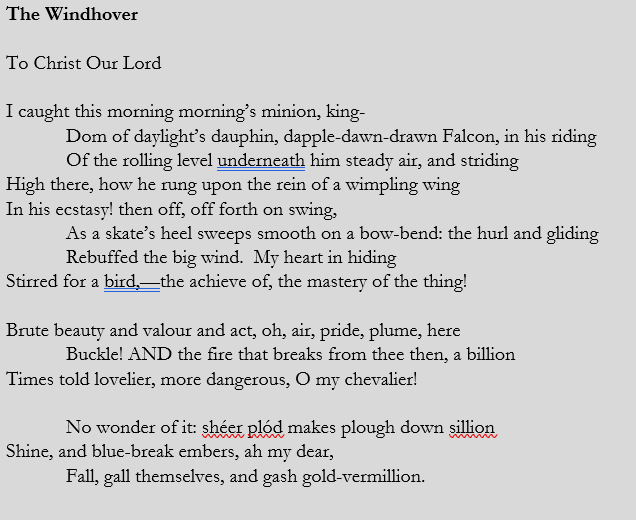

Reverence for Life: The Windhover

For those readers who find me too trenchant, here’s the other side

—Gerard Manley Hopkins, 1877

That masterpiece of poetry was dedicated, by Hopkins, to one of the three iterations of the Christian G-d. The reverence for that bird, and its magisterial motion, can bring me to tears. And with Hawking’s synthesized Einsteinian equation, who do we thank for such a performance? Well, that begs the appearance and purpose of beauty—a subject already addressed.

In the end, the essential fact about faith, ritual, and reverence is that we need all three to live a well-spirited life but none of those three requires nor benefits from absolutist dogmas. On the contrary, at their best, they will necessitate a compassionate grasp of Heraclitus’ river.

Thank you for thinking and acting. More next week. Be well.

Summary

- Some form of faith, ritual, and reverence is essential to a well-spirited life—science backs this up.

- Wokeism excludes people based on socio-economic, racial, and class-based criteria while classical liberalism accepts all people—as human beings—so long as they practice basic civility.

- The science of the beginning of the universe tells us there was no such thing as time before the Big Bang. The Big Bang was so intense and instantaneous that there was no time or place from which G-d could have come or existed—there was simply a still nothingness.

- Without G-d, whom do we thank for beauty, life, and love? Gerard Manley Hopkins shows us two ways; one Christian, one natural.

- It seems to me that a metaphysical appreciation of nature, beauty, life, and love is the turning point we need to move from this point of agony forward into well-spiritedness.

Sources Referenced:

Hawking, S. (2018). Brief Answers to the Big Questions. Random House.

Hopkins, G. M. (1877). The Windhover in Allison, A.W., Barrows, H. Blake, C.R., Carr, A.J., Eastman, A.M., and English, H.M. Jr. (1975). The Norton anthology of poetry (Revised shorter ed.). W.W. Norton & Company.

Pinker, S. (2014). The Village Effect: How Face-to-Face Contact Can Make Us Healthier, Happier, and Smarter. Vintage Canada.

Comments