Helplessness, Stress, & Learned Resilience

12 October 2024

Last week’s intervention was walking around the block to arrest rumination while saying to yourself, knowing a tool is not the same as practicing a tool. Please stop walking now.

As some of you know, much of what you’re reading forms part of the manuscript of a book I’m trying to complete. It’s called Individual Excellence: The 4Ps of a Well-Spirited Life. Those 4 Ps are people, product, purpose, and processes. The writing is in the middle of processes.

This portion of the writing, ties together themes around stress. Those themes have been discussed by McGonigal, Perry & Winfrey, and Seligman. We proceed in the opposite order. These ideas are important because it’s impossible to create a well-spirited life if you are unable to deal effectively with stressors.

Now, imagine that you are so aroused by some terrifying event, that you’re ready to fight or run, most of the time that you’re awake. An analogy is an unmoving car with its engine revving at 4,000 RPM for hours at a time. That car is representative of the human condition of fight, flight, or freeze. Helplessness is freezing.

What Maier got to, and what Seligman took such pains to describe, is that our default, as human beings in nature, is helplessness. The selective advantage of helplessness is that we often lived through life-threatening situations. The selective disadvantage is that we lived but with a lot of deeply unactualized potential which tends to transmit itself down the generations. So Maier’s point was that we learn control by unlearning helplessness. Or, per Seligman’s description,

The takeaways merit more discussion. In the last few weeks, we’ve discussed the first, the relationship between arousal, performance, stress, and anxiety. This week we’ll continue by discussing what Seligman called higher cortical processes. What he wrote is that our higher cortical processes inhibit, which means dampen or reduce, our sense of helplessness.

I have to confess that the hair at the back of my neck stood up when I wrote that sentence. The reason is a wild circularity in time between Seligman’s premise for positive psychology and Aristotle’s differentia between animals and humans. That differentia—that which makes one thing distinctly different from another—was rationality. Rationality is what happens—by choice—in the cortex of the human brain—the only class of brains in the traceable history of the universe to manifest this capacity. So we have two propositions:

2. Reason happens in the cortex, the highest or last part of the brain to have evolved i.e., the most recent.

Perry & Winfrey (2021) provided the most easily understood explanation. I will explain it using an example they provided.

An older U.S. veteran and his girlfriend were walking down a main street on a nice night after dinner. Without apparent cause the man ran and hid behind a nearby car, laying face down, hands covering his head. His girlfriend found him sweating, highly anxious, with his heart pounding. The next day they went to see the man’s psychiatrist, Dr. Perry, because the veteran felt he needed to have a professional relate the experience to his girlfriend, so she wouldn’t think him crazy.

The vet had seen a lot of active combat three decades earlier. Since then, he was a drinker and a binger, depending on what was happening within. What had happened that night, on the main street, is that a loud motorcycle had gone by and backfired, sounding like gunfire.

Psychosomatically, that is, in his mind and body, the vet was back in Korea, unarmed, and afraid for his life. Here’s why this story is important: Did that man think his way onto the parking lot pavement or was that a preconscious reaction?

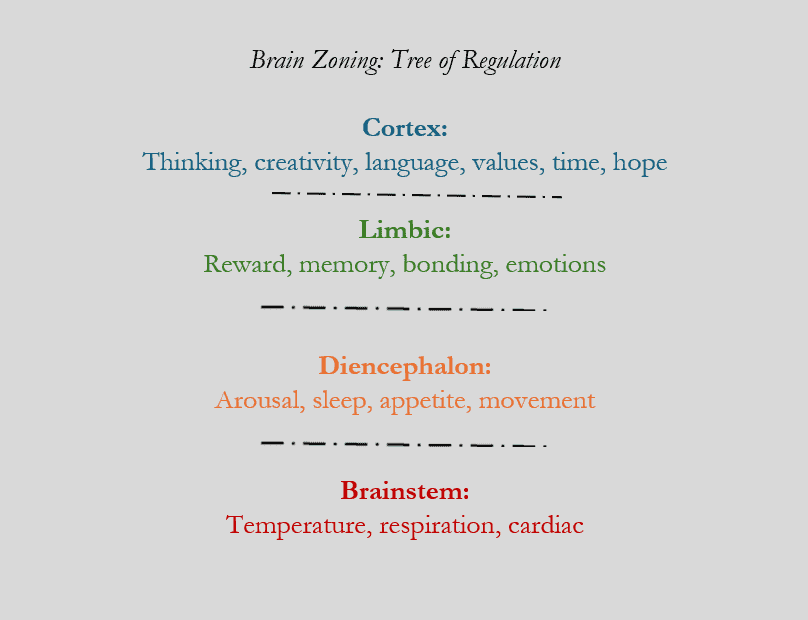

Here are the relevant levels of the brain:

Figure 1: A Model of the Brain, after Perry & Winfrey, 2021.

If you were paying close attention, the description of that terrified man included the fact that his heart was pounding (brainstem), he was sweating (brainstem), and he was anxious (diencephalon). As life-threatening stimuli affect us from the bottom of the brain upward, this fellow didn’t think his way onto the pavement, he moved (diencephalon) at rapid speed on a preconscious impulse.

“Input from all of our senses…first comes into our brain in the lower areas. None of our sensory input goes directly to the cortex; everything first connects to lower parts of the brain (Perry & Winfrey, 2021, p. 26).

That reaction occurred because that vet had been traumatized decades earlier with arousal levels unable to cope with such a noise. With therapy, he would (and did) learn to self-regulate and then to realize he was no longer in military combat zones.

For those not traumatized, it is known that a strong stressor temporarily shuts down the higher regions of the brain to such an extent that telling time, on your watch, is a challenge. That’s unhealthy arousal. But, equally, it’s our body’s way of saying, this might take you out—get to a safe place—NOW! In other words, with life-threatening stress, telling the time, might not be that important so the brain’s emphasis moves downward from the cortex to the brainstem which changes your hormone mix, allowing you to move.

Now, in a previous issue of this blog, I provided a definition stating that stress is what arises when something you care about is at stake (McGonigal, 2016, p. xxi). Perry’s definition seems to agree with that but takes it further: “Stress is what occurs when a demand or challenge takes us out of balance—away from our regulated set points” (Perry & Winfrey, 2021, p. 48). They unpacked this by stating that balance is the core of health, itemizing factors such as being in balance with friends, family, community, and nature. But they go further.

They also plug inputs and outputs into the diagram of the brain levels seen below. Hormones, our autonomic nervous systems, neuroimmunology, interoception, and sensory inputs are all implicated as factors contributing to how we respond to our stressors. While those factors are obviously important, our purpose is less physiological and more explanatory. I’ll leave you with one more diagram to explain this.

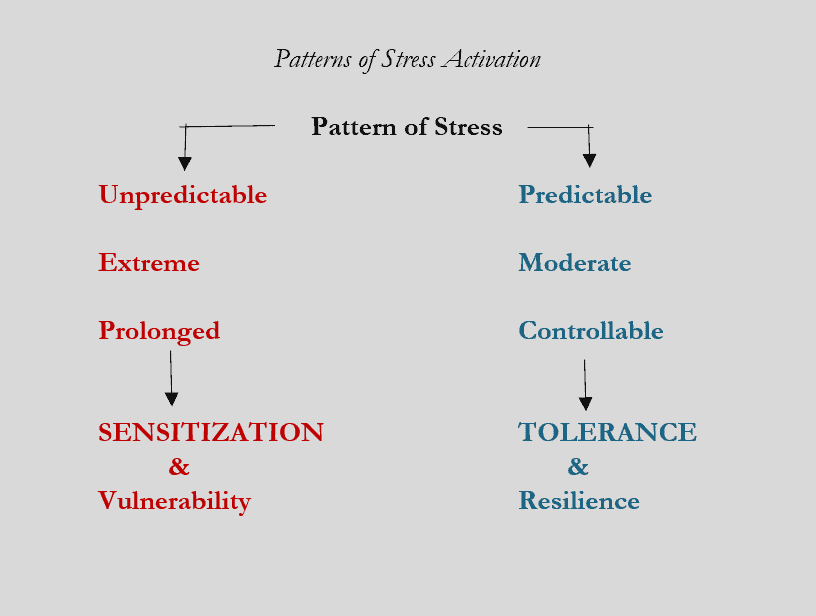

Figure 2: Stress Activation Patterns, after Perry & Winfrey, 2021. [Image]

This is what comes of an understanding of helplessness, which is very relevant to trauma, and where and why, within the brain, different functions occur. If you look at Fig. 2, you can see what therapy or repeated rehearsal, as in high level athletics, could do. What was once unpredictable, extreme, and prolonged, can be reinterpreted and entrained as predictable, moderate, and controllable, thus fostering tolerance and resilience.

Here are the main points we covered:

Summary:

- It’s impossible to create a well-spirited life if you are unable to deal effectively with stressors.

- Unhealthy arousal is like a stationary car revving for hours at 4,000 rpm.

- Helplessness is our default response to terror.

- Helplessness becomes habitualized ruining lives, and even generations of lives, within traumatized families.

- We reason by choice, not by default.

- The brain is hierarchical such that reason happens in the cortex, the highest or last part of the brain to have evolved i.e., the most recent.

- Sensory data gets first place in the brain when tied to major stress, reason gets last place.

- A balanced life—and balance is the essence of health—deals with stressors as predictable, moderate, and controllable. Most importantly, this can be learned.

Thank you for thinking and acting. More next time. Be well.

Sources Referenced:

McGonigal, K. (2016). The Upside of Stress: Why Stress is Good for You and How to Get Good at It. Avery, Penguin Random House.

Perry, B. D. & Winfrey, O. (2021) What Happened to You? Conversations on Trauma, Resilience, and Healing. Flat Iron Books.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2018). The hope circuit: A psychologist’s journey from helplessness to optimism. Public Affairs, Hachette Book Group.

Comments