Stress, Anxiety, & Practice, Practice, Practice

5 October 2024

Last week’s intervention was using maybe in response to negative thoughts. Maybe I’m not a klutz. Maybe I’m not just an addict. Maybe I can change. The subject was stress and its relationship to arousal, helplessness, and recovery. I’ve had some questions from viewers. My supposition is that, if one person is asking these questions, ten others have thought about them. So, this week’s work aims to clarify more about stress and stressors.

- What’s normal stress?

My first inclination is to answer this question with an approach used in therapy: the distinction between normal and abnormal is statistical and therefore not so helpful. That distinction is unhelpful because what’s normal for one person is completely abnormal for another. The more impactful question, which may underly What’s normal stress? Is What is the distinction between healthy and unhealthy stress?

People familiar with this channel will know that the word eudaimonia, Greek for well-spiritedness is my choice of an optimum state of being. Happy is like the gorgeous but fleeting scent of magnolias in spring—here and gone, here….and gone. Well-spiritedness is an approach to life—meet your challenges with optimism, courage, and resilience.

The prefix in eudaimonia, eu, in Greek, means well. That is also the prefix used for good stress: eustress. Eustress, interestingly, is less about the content of the stress than it is about how we meet that stressor. To answer that viewer’s question, in their terms, normal stress is stress we can deal with in a health-promoting process. Stress that causes permanent arousal, intrusions, difficulty sleeping, and isolation is traumatic stress and is not helpful. That said one person’s arousal-inducing stressor is another’s day-to-day stressor. It’s about us, not the stressors.

2. Can we reach these peaks and valleys depending on the situation?

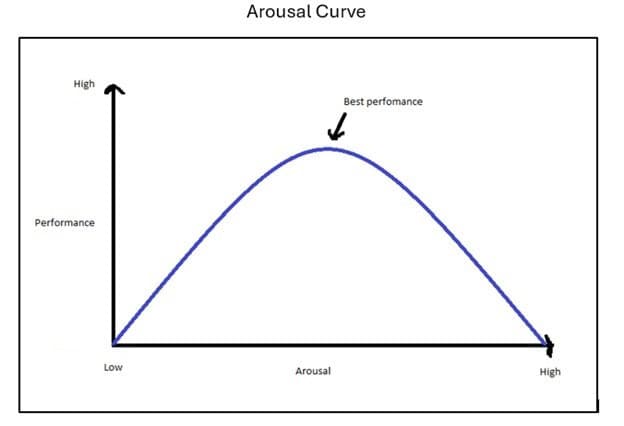

The peaks and valleys referred to in the question are probably those on the arousal curve, below:

Here’s why this graph matters. On the lower left, and lower right, we see the two worst relationships between performance and arousal. Lower left, no motivation (zero arousal) and zero performance. Lower right, very high arousal and very poor performance because the anxiety/over-arousal prevents effective performance. The sweet spot is between the word performance (at the y-axis) and the words best performance at the centre of the curve. That’s our target.

The direct answer (Can we reach these peaks and valleys depending on the situation?) is Yes, our internal states can be performance-enhancing or performance-destroying. This is why I’m writing about process. If we learn and practice health-enhancing processes, we ought be able to meet most stressors with a performance-enhancing set of practices. For example, fully accept the reality of the situation—and the range of possible outcomes, as dire as they may be.

The example that comes to mind is that of U.S. Admiral James Stockdale who new, as he parachuted into enemy territory from his burning plane, that he was entering the world of Epictetus i.e., he had a copy of Epictetus’ Enchiridion with him, and he deployed the lessons brilliantly through seven years of torture and captivity. Fellow prisoners, who had no such processes, were not so fortunate and never saw home again. Stockdale did.

Many of those who never saw home filled themselves with baseless hope: “We’ll be out by Christmas.” Stockdale reported that they died of broken hearts. What he told himself is that his only choice was to resist without dying and to have no expectations other than that he could control most of his reactions.

If we list some of these factors, they look like this:

- Fully accept the reality of your situation

- List the range of possible outcomes, no matter how dire

- Be disciplined in your self-dosing of emotion

- Create repeatable patterns of exercise, connection, and changed environments

- Don’t nurture unrealistic hopes

That’s a tentative list (that may be modified as my writing and thinking progresses) but it’s a starting point. What that starting point does is hopefully enable you to safely navigate both the peaks and valleys in favour of a well-spirited, goal-directed forward motion.

3. I’m stressed, distracted, and incoherent—if I know the tools, why am I so fearful and anxious?

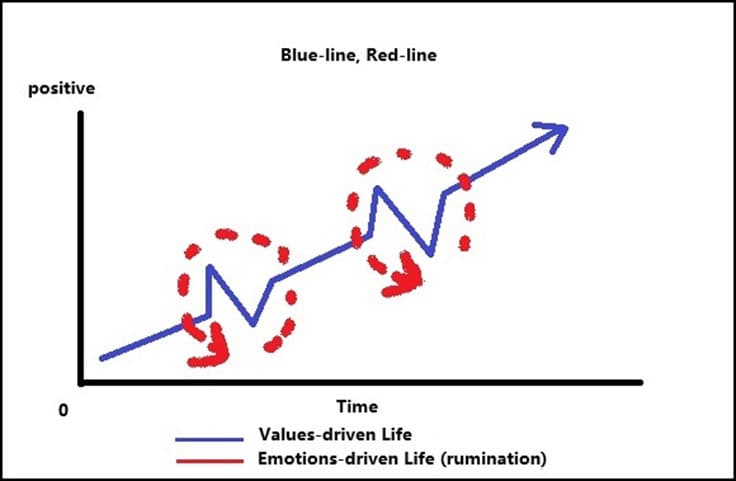

Here’s a way to visualize where you want (and don’t want) to be:

On this curve, you can see two low points, where the blue line starts and stops. At the lower left, one has zero motivation and poor performance; on the lower right, one has overwhelming anxiety and poor performance. The sweet spot is between the peak of the curve and the midpoint of the y-axis between the top and halfway up.

This diagram characterizes regulated versus dysregulated emotions and how dysregulation can stall a perfectly fine human life. There are a few points to focus on. First, notice that the blue-line, which represents a values-driven life, is pointing upward. My sense is that a human life never really unfolds horizontally—we’re moving forward or we’re moving backward. Secondly, there’s an angle and a momentum at which this life is moving (think of the blue line as a vector). The angle and momentum change constantly. Thirdly, there are jagged blips—or challenges on every blue line—those are the hurdles we have to defeat or acquiesce to. Finally, there are red lines circling the two jagged blips—those lines represent abandoning your values-driven life in favour of an emotions-driven life. As the drawing indicates, that broken red line just keeps on spinning around the blue blip. In psychology, that sort of compulsive anxiety has come to be called rumination. We chew and chew on the same issue with no real progress.

So, I hear question #3, I’m stressed, distracted, and incoherent—if I know the tools, why am I so fearful and anxious? a few issues rise to the top. Probably the most important is becoming aware of one’s own dysregulation. If you’re ruminating, change something, especially something physical like your environment or your rate of movement. Go walk around the block.

While you’re walking around the block, please repeat this mantra: knowing a tool is not practicing a tool. To practice a new tool is awkward, uncomfortable, and makes you feel a bit silly. But there’s something important happening. In that discomfort are signs of growth. Afterall, if growth were easy, I wouldn’t have a job.

Finally, the word incoherent deserves some attention. One of my first signs of anxiety is the rate, volume, and dynamics of a person’s speech patterns. Faster, louder, and more staccato signals higher anxiety. Simply reducing the tempo, volume, and rhythm of your speech can reduce your sense of incoherence significantly.

To Summarize

- Whether a stressor is helpful or harmful is not about the stressor, it’s about us and our perception of the stressor.

- Our internal states can be performance-enhancing or performance-destroying.

- Fully accept the reality of your situation.

- List the range of possible outcomes, no matter how dire, and consider each. First the worst.

- Be disciplined in your self-dosing of emotion.

- Create repeatable patterns of exercise, connection, and changed environments.

- Don’t nurture unrealistic hopes but neither are we well-served by despair.

- Without practical routine-based discipline, we abandon values-driven life in favour of an emotions-driven life = rumination (Cf. #5, above).

- If you’re ruminating, change something, especially something physical like your environment or your rate of speech or movement. Walk around the block. Now. While you’re walking around the block, please repeat this mantra: knowing a tool is not practicing a tool. Practice the tools. Daily.

That is also your intervention for the week: Don’t just know your tools, use them. Daily.

Thank you for thinking and acting. More next week. Be well.

Sources Referenced:

McGonigal, K. (2016). The Upside of Stress: Why Stress is Good for You and How to Get Good at It. Avery, Penguin Random House.

Perry, B. D. & Winfrey, O. (2021) What Happened to You? Conversations on Trauma, Resilience, and Healing. Flat Iron Books.

Resick, P. A., Monson, C. M., & Chard, K. M. (2017). Cognitive Processing Therapy for PTSD: A Comprehensive Manual. The Guildford Press.

SMARTRecovery.org

Comments