Stress, Arousal, Helplessness, & Recovery

28 September 2024

If this is easier to understand in a video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XtNOQyjHbw0

Last week’s intervention was making a mistake and saying, Excellent! and then thinking of at least one advantage resulting from that mistake. The subject was stress and its relationship to trauma, addiction, and burnout. We’re going to dig into those relationships from the perspectives of arousal and helplessness.

The main premise of last week’s discussion was that stress is a manageable phenomenon. And that’s true as long as healthy conditions prevail. But, once we go from self-regulating normalcy to dysregulated, we’re no longer managing stress—it’s managing us.

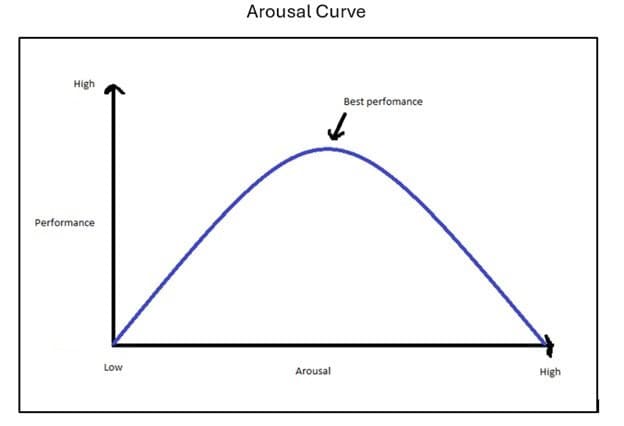

Here’s the arousal curve:

On the x- or horizontal axis is arousal. On the y- or vertical axis is performance. If you follow the bell-shaped curve, you see that performance maxes out at the top of the bell. As you increase arousal past the top of that bell, your performance starts dropping as your anxiety increases.

Now we’re speaking in the context of trauma, addiction, and burnout so let’s relate that high anxiety and arousal to those conditions. What cognitive processing therapy says is that in normal day-to-day life, our arousal and our intrusive thoughts subside and become part of autobiographical memory.

However, if you experience something that messes with you in a big way – i.e., messes with your basic assumptions about people, life, rightness etc., the intrusive thoughts keep recurring and your native arousal rises to unhealthy levels i.e., you enter the realm of post-traumatic stress. There are at least three modes of therapy that can help you to integrate and bring renovated meaning to those intrusions, which will bring your arousal back down. Now, let’s take a short break from arousal and look at resilience.

Up until the middle of the 20th-C, most psychology was focused on pathologies, or on the troubles & behaviours psychology and medicine had catalogued and classified as mental disorders. A whole stream of new thought emerged, post WWII, starting with Maslow, Rogers, Erikson, Frankl and others. By the 1960s, those seminal ideas had changed the questions some psychologists were asking. That change of interest was characterized by one main question: What can we do to improve the psychological lives of most people rather than cataloguing and treating clusters of symptoms for a small group of people? This was the beginning of positive psychology.

Martin Seligman, one of the leaders of this new wave in psych., along with Steve Maier, and others, was trying to understand learned helplessness. Over more than 30 years, and with Maier taking a deep dive into neurology, they realized they had asked the wrong question. What Maier demonstrated is that it had been selectively advantageous for our ancestors to be helpless in the face of massive adversity. It wasn’t helplessness that needed to be unlearned, it was control and resilience that need be learned to create well-spirited lives.

As I’ve mentioned and written before, about a year or two into facilitating SMART Recovery meetings for addiction, I started seeing a common pattern: people in those groups had a hard time accepting a compliment. Eventually, I just started asking SMARTies about this. What is it that stops you from accepting that compliment and just saying thanks? With considerable emotion, these recovering souls would tell the group that they’d done so many bad things and hurt so many good people that they were no longer worthy of a compliment. Think about that.

If you believe you’re not worth a compliment regarding something you did today because of a mistake you made yesterday, or ten years ago, you are not capable of self forgiveness. What I quickly realized is that we needed to do some work on self-compassion. And guess what? One of my early practicum clients had suffered decades of PTSD and was also incapable of saying anything good about themselves. The premise I’m working toward is that a lack of self-compassion latches on to those people with trauma and addiction and is either correlated with helplessness or an effect or cause of that parallel condition.

If the clients and SMARTies I know are unable to accept a single compliment, what is the nature of their self-talk? Their self-talk is destructive, acidic, and corrosive of their souls. A corroded soul in a pool of acidic self-hatred does not embrace the sun, the rain, or the wind. That soul isolates, fears, condemns, cries…Until you believe you are worthy of life, self-compassion, self-control, and resilience are empty dreams.

That was our necessary digression. To tie helplessness to arousal, we'll look at a quote from Bruce Perry: “The journey from traumatized to typical to resilient helps create a unique strength and perspective. That journey can create post-traumatic wisdom” (Perry & Winfrey, 2021, p. 200). Intrusions and arousal, two of the four hallmarks of PTSD, encourage sufferers to increase isolation, which increases helplessness. Think of the Maté-Hari message: the opposite of addiction is not sobriety, the opposite of addiction is connection. Connection and isolation are opposites.

Remember last week’s message: addiction is a type of avoidance. Avoidance is the primary hallmark of PTSD. Disengagement, depression, and hopeless cynicism are the hallmarks of burnout. To grow through any or all of trauma, addiction, or burnout requires re-connection with people, places, and things that matter to you.

To reconnect takes massive courage and that courage starts with one semi-optimistic word: maybe. Saying this is your intervention this week: Maybe I can forgive myself, maybe I can cut down, hell, maybe I can even stop.

- We have choices about how we recognize, characterize, and manage our stress.

- Stress provokes arousal which has an optimum point, after which it becomes destructive.

- In normal day-to-day life, a sudden stressor brings increased arousal and intrusive thoughts, but these subside and become part of autobiographical memory.

- When a stressor provokes a deeper level of fear, horror, guilt or shame...anxiety, high arousal, and intrusions increase to the point of post-traumatic stress (PTSD).

- We tend to become helpless in the face of apparently overwhelming odds, which means, that for a well-spirited life, learning and practicing resilience and self-compassion is vital

- Moving from traumatized to typical to resilient invariably involves connection, the opposite of addiction because connection decreases the need for avoidance.

The publication date of this blog is the birthday of the man whose life directed me back, sometime around the year 2000, to the culture of addiction into which we had both been born. I hope you have a chance to see this and to know, this one’s for you, buddy.

Maté, G. (2018). In the realm of hungry ghosts: close encounters with addiction. Vintage Canada.

Neff, K. (2023). Self-compassion.org

Perry, B. D. & Winfrey, O. (2021) What Happened to You? Conversations on Trauma, Resilience, and Healing. Flat Iron Books.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2018). The Hope Circuit: A Psychologist’s Journey from Helplessness to Optimism. Public Affairs, Hachette Book Group.

SMARTRecovery.org

Comments