Individual Excellence: Part II, Process 7

13 July 2024

Today’s blog is one of a chain from an in-process book entitled, Individual Excellence: The 4Ps of a Well-Spirited Life. What follows is the seventh passage of Process, the second of four sections of that book. Last week five lists were presented here. This week discussion of various points of comparison, between the lists, begins below.

PART II: Process

An Epistemological Footing

I like and agree with Covey’s statement that first things ought come first. I don’t see positive evidence of the first things I would like to see first except in my eclectic list of Aristotle’s virtue ethics. What’s missing is epistemology—the study of knowledge.

Each of theses five sets of values skirts how we know and what we know, but none puts it front and centre. This may be the unique selling proposition of the book you’re currently reading: epistemology must come first. It must come first because without agreement on what we’re talking about, and that subject’s existential attributes and boundaries, we’re at sixes and sevens, apples and oranges, or truth and dogma.

The Ten Commandments imply that truth exists in the 8th commandment, Neither shalt thou bear false witness against thy neighbour. That adherence to truth is inferable: If we cannot bear false witness, we must be able to bear true witness. If we can state the truth as witnesses, the truth is evident i.e., it exists and it is communicable.

Aristotle puts it right out there: truthfulness. But in in Logic and Metaphysics, he was the first to define a law of identity: A = A. What that equation implies is that a thing is itself. This is the basis of knowledge, science, justice, and meaningful argument. This is why epistemology must be at the root of a thoughtful individual’s processes.

Covey’s inclusion of the statement that effective people must Seek first to understand, then to be understood reads more like rhetorical strategy than truth-seeking but that is probably an uncharitable view. More charitably, Covey has emphasized understanding and in the latter half of fifth principle he states the importance of understanding another’s perspective. One reading is that we seek such understanding to arrive at satisficing compromises. A more skeptical reading is that we ought seek to understand needs and perspectives of others to ensure we are both on a similar epistemic platform. If not, the earlier you know this, the more effective your decision-making will be. Why? To know the truth is to be in accord with reality. To be in accord with reality is to be one with the Earth, to actualize.

Peterson’s list includes three consecutive points (nos. 8, 9, & 10) that get near the primacy of epistemology:

- Tell the truth—or, at least, don’t lie;

- Assume that the person you are listening to might know something you don’t; and

- Be precise in your speech.

To tell the truth, you must believe the truth can be identified and communicated. To assume that others possess knowledge that you don’t, is to honour and understand that knowledge exists, is useful, and communicable. To bring precision to one’s communication is to acknowledge that precision in communication is possible because there are identifiable existents apprehended and whose meaning and attributes are transferred within language.

Seligman is vaguer: True engagement fosters flow and full presence. True engagement is engagement of one’s full being with the subject at hand. For there to be true engagement, there must first be identifiable (and agreed upon) reality to engage with. At least as significant as that reality is the agreement that humans possess the means of knowing, discussing, and understanding that reality.

The latter part of Seligman’s second point (above) is noteworthy. If full engagement brings flow and full presence, then full engagement is mindfulness. As I understand mindfulness, it is being with all channels open. To be fully mindful is to be where your feet, nose, ears, eyes, tongue, and mind are, but with an openness to acceptance that fosters that joyful engagement that Csikszentmihalyi labelled flow.

…in moments such as these what we feel, what we wish, and what we think are in harmony. These exceptional moments are what I have called flow experiences. The metaphor of “flow” is one that many people have used to describe the sense of effortless action they feel in moments that stand out as the best in their lives. Athletes refer to it as “being in the zone,” religious mystics as being in “ecstasy,” artists and musicians as aesthetic rapture. Athletes, mystics, and artists do very different things when they reach flow, yet their descriptions of the experience are remarkably similar.

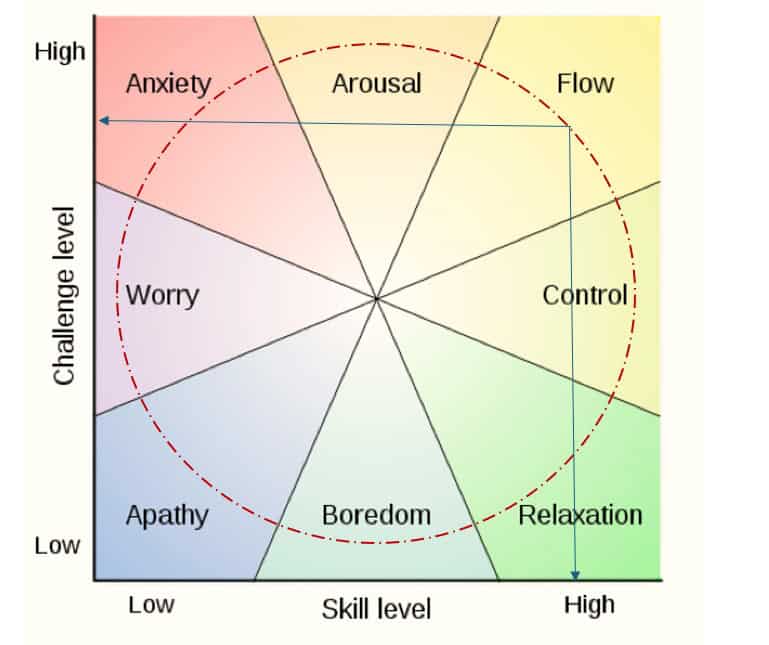

Flow tends to occur when a person faces a clear set of goals that require appropriate responses…Flow tends to occur when a person’s skills are fully involved in overcoming a challenge that is just about manageable. Optimal experiences usually involve a fine balance between one’s ability to act, and the available opportunities for action (Cf. Fig. 7.1). If challenges are too high one gets frustrated, when worried, and eventually anxious. If challenges are too low relative to one’s skills one gets relaxed, then bored. If both challenges and skills are perceived to be low, one gets to feel apathetic. But when high challenges are matched with high skills, then the deep involvement that sets flow apart from ordinary life is likely to occur. (Csikszentmihalyi, 1997, pp. 29-31)

Figure 7.1, Challenges vs Skill Levels, Adapted from Csikszentmihalyi, 1997, p. 31)

Csikszentmihalyi has added to our roster. He stated that we need a clear set of goals and appropriate responses in order to enter this optimum state of being. To have a clear set of goals and appropriate responses requires self-awareness and honesty. Like all epistemic processes, self-awareness and honesty require emotionally and intellectually attuned inner ears.

This is a metaphor I use with clients. Given that I deal with addiction and trauma, avoidance and denial are often front and centre in a client’s epistemic processing. What that means is that instead of accepting and analysing facts, situations, and opinions, as they present themselves, people suffering addiction and/or trauma seek to push awareness of such facts, situations, or opinions well out of reach as quickly as possible.

Sometimes that pushing away is done with psychoactive drugs (tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, meth, heroine, crack…) and sometimes “ugly” reality or pain are pushed away with behaviours like sex, shopping, gambling, or violence. What all of these have in common is that they buy time and distraction from reality. Again, we are face to face with epistemology: how we know.

If our ego strength is too low or too fragile, we haven’t the emotional cycles to deal with our own failures. When this happens, we avoid. And, to be clear, we all do this but a healthier person avoids or denies on a very temporary basis i.e., I’m not dealing with this right now. But later in the day, or within a permissible time frame, a responsible, well-functioning person deals with their challenges. Why? If we don’t deal with our challenges, they stack up rather quickly.

Let’s take this one step further. Imagine not dealing with your natural gas bill in January in Canada because you need the money for something else at that moment. The day you avoid the need to pay the gas bill, you also scrape your car while talking on your phone at a Tim Horton’s drive-through. The phone call you were taking with one hand was from your lawyer who has just received notice of a further claim from your wife, who has recently left you. One of your life issues is an addictive relationship to alcohol. By the time you leave the drive-through you have a case of what the addictive community calls the Fuck-Its.

The Fuck-Its arise when we stack problems rather than facing them one at a time. That money we failed to send the gas company now goes into a week’s supply of vodka or beer. That’s what the Fuck-Its are about; they tell us the problems in life are too overwhelming to deal with and this crazy idea of facing life without compulsive sex or crack is way too much so Fuck It, I’m using. This is one form of harmful epistemology: we lead with our emotions, not our values.

If you look at the quote from Csikszentmihalyi, a couple pages back, particularly the first line of the second paragraph, you see the requirements of flow: full, magnificent involvement with life: “... a clear set of goals that require appropriate responses.” Look at the unfortunate soul in the drive-through. He’s avoiding clarity, goals, and appropriate responses in favour of another self-indulgent freak-out that moves his rook backward on the board.

Such behaviour is the diametric opposite to intentional actions aligned with long- and short-term goals. Csikszentmihalyi (1997) divided people, on any given day, into three groups. Group #1 does what they do because they wish to do those things. Group #2 does what they do because they feel they must while group #3 acts as they do because they believe they have nothing better to do. Those in group #3 have the highest scores for psychic entropy which is mental chaos almost certainly heading downward.

Interestingly, having nothing better to do or believing you have to do something are both states of mind leading to wandering thoughts via boredom.

Intentions focus psychic energy in the short run, whereas goals tend to be more long-term, and eventually it is the goals that we pursue that will shape and determine the kind of self that we are to become…Without a consistent set of goals, it is difficult to develop a coherent self. It is through the patterned investment of psychic energy provided by goals, that one creates order in experience. This order, which manifests itself in predictable actions, emotions, and choices, in time becomes recognizable as a more or less unique self. (Csikszentmihalyi, 1997, p. 23)

Please notice that we began with a description of psychic entropy and ended with a set of practices fostering psychic order. Csikszentmihalyi got close, but neither he, the Bible writers, Covey, Peterson, Seligman, nor virtue ethics explicitly identifies the primary role played by epistemology, knowing what and how we know. What do you do now that you know? You question your own assumptions until you hit undisturbed soil—and then you start building upward.

To be continued next week.

Dan Chalykoff is a Registered Psychotherapist (Qualifying). He works at CMHA-Hamilton and Healing Pathways Counselling, Oakville, where his focus is clients with addiction, trauma, burnout, and major life changes. He writes to increase (and share) his own evolving understanding of ideas. Since 2017, he has facilitated two voluntary weekly group meetings of SMART Recovery. Please email him (danchalykoff@hotmail.com) to be added to or removed from the bcc’d emailing list.

References:

Covey, S. R., (1990). The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: Restoring the Character Ethic. Simon & Schuster.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1993). The Evolving Self: A Psychology for the Third Millennium. HarperPerennial Modern Classics.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1997). Finding Flow: The Psychology of Engagement with Everyday Life. Basic Books.

Comments