Boundaries II

27 May 2023

This blog follows another, written in March, last year, available here: https://understandings.ca/2022/03/16/boundaries-and-adulthood/ Both concern the role of boundaries in the lives of families and individuals. In the previous entry, we looked at one of two main failings of boundaries in families. The one we looked at was boundaries that are too permeable or diffuse i.e., children (or spouses, siblings) are not encouraged to foster sufficient independence and autonomy (individuality) because others consistently invade their boundaries telling them how they should be. Truscott & Crooks (2021, p. 143) indicate that the extreme end of this side of the boundary’s continuum is incest—the child no longer has control over her own body.

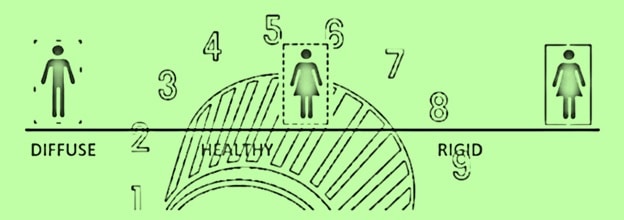

The second variant is boundaries that are too rigid, fostering parental indifference to children, which means insufficient attachment. From the child’s perspective, the result is feeling uncared for, ignored, unloved, and without supportive guidance. At the extreme end of this side of the boundary’s continuum, that means willful neglect. Here it is graphically:

Figure 1, Boundaries Continuum (Naylor, 2021)

Another therapist, Barnett (2023) looked at boundaries as spatial. Explanatory questions include: Where do I begin and end? How comfortable am I if you touch my hand, my leg, my face? Do you expect me to share my innermost feelings? Per the title of her book, The Heart of Therapy: Developing Compassion, Understanding and Boundaries it’s clear that Barnett places boundaries at the top of the hierarchy of psychotherapeutic values. I note this fact for a reason.

As I prepared this blog, I looked at the manuals therapists use. I have manuals for Dialectical Behavioural Therapy (DBT), Acceptance & Commitment Therapy (ACT), and Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT). I also looked at some disorder-specific manuals for Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) and, being a recent graduate of two psychology degrees, some of my more basic textbooks. None—not one—had a word on boundaries. What this tells me is one of a couple of things: boundaries can’t be easily identified in quantitative research and/or they’re devilishly hard to define.

Going with the hard-to-define (which also supports hard to nail down in experimental design) leads pretty quickly to the self. My final counselling psychology paper was on dimensions of the self as a concept and as exemplified in particular qualitative research. There are philosophers of mind, and probably schools of psychology (behaviourist et al.), who flat out deny the reality of any existent called a self. This makes sense in terms of our current discussion: what is this thing whose edges we are seeking to understand? If the thing itself doesn’t exist, how can that thing have inner and outer limits? Let’s see.

If we return to Naylor’s helpful diagram (Fig. 1, above) some interesting inferences are possible. Look at the broken rectangle on the rigid (right) side of the continuum. In order for that boundary to flex it literally breaks into two halves. Go to the other side and you see more openings than limits. Alternately, the healthy figure has a multifaceted boundary with openings and limits on all dimensions. Metaphorically, those three diagrams tell a lot of the story.

If a parent has so porous a set of boundaries that they are unknowable (diffuse), the children of that parent are raised with, at best, inconsistent to nonexistent boundaries. As above, that child is being raised without boundaries which is to be neglected and uncared for in many important respects.

If a parent has boundaries so rigid that that parent needs to crack wide open in order to be flexible, that parent is going to find it much easier to draw hard and fast limits that are set to suit the parent’s (deeply compromised) peace of mind, not the children’s welfare.

Where the real craft of parenting occurs is in those with healthy boundaries. Healthy boundaries demand a difficult but self-respecting attitude toward constant flexure. Any parent who has raised two or more children knows that each child has individual requirements i.e., no two children are completely alike. This means that while valuing and protecting her own integrity, and the integrity of the marriage and home, that parent has to compassionately meet the needs of each of her children while being able to eloquently defend her differential choices in the savage jurisprudential arena of sibling rivalry.

There’s more to be written on this but we’ll end with an observation. I believe it was Carl Jung who wrote that psychotherapy is little more than a substitute for absent parenting. My experience indicates there is truth in that statement which means, those parents who adopt, defend, and articulate the need for healthy boundaries are raising resilient, psychically well-balanced children and citizens i.e., there is no more important role than that of thoughtful, compassionate, boundary-conscious parenting.

Dan Chalykoff is (finally!) a Registered Psychotherapist (Qualifying). He works at CMHA-Hamilton and Healing Pathways Counselling, Oakville, where his focus is clients with addiction, trauma, burnout, and major life changes. He writes these blogs to increase (and share) his own evolving understanding of ideas. Since 2017, he has facilitated two voluntary weekly group meetings of SMART Recovery. Please email him (danchalykoff@hotmail.com) to be added to or removed from the Bcc’d emailing list.

References

Barnett, L. (2023). The Heart of Therapy: Developing Compassion, Understanding and Boundaries. Routledge.

Naylor, L. (2021, April 14). Boundary Continuum. https://www.laveldanaylor.org/blog/boundary-continuum

Comments