Maslow Redux: Safety

25 February 2023

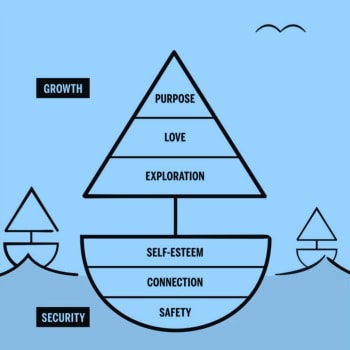

Looking at the little sailboat, below, Figure 1, the next few blogs with go through all the parts of the hull and then the sail, working skyward. This week we’re deep in the water looking at the revised safety needs Kaufman (2020) wrote about.

(Image: Andy Ogden in Harper, 2020).

Two years ago, I wrote about Maslow’s most fundamental needs based on what I then knew of the ideas, and what had been accepted as his message, since his death in 1970 (https://understandings.ca/2021/05/26/the-basics-physiological-needs-in-maslows-hierarchy/). Those essays covered responsibility and the basics such as food, water, air, sleep, warmth, and exercise—essentially, physiological needs.

Under safety needs (https://understandings.ca/2021/06/02/maslows-safety-needs/) the basic list consisted of security, stability, health, shelter, money, and employment. The conclusion reached, in 2021, was that we know our safety needs are met when we’ve stopped dwelling on them i.e., if you have all of those things in your life, and are not worried about losing them, you focus on other things, hopefully growth-based values.

In the last blog, we highlighted environments. What ought be emphasized is that we all have—and maintain—internal and external environments. Whereas the first 50 years of Maslovian thought were based on physiological needs, Kaufman’s (2020) revision changes the focus from external physiology to internal culture.

One of the missing pieces of my education in psychology was the term ACEs. Adverse Childhood Events were, according to Harvard University’s Centre of the Developing Child (2023, p. 1) identified by Centers for Disease Control and the Kaiser Permanente health care in 1995. ACEs then included “…various forms of physical and emotional abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction.” Kaufman (2020) discussed these but not under the ACEs heading. He then explained that such harms lead to formative action within each person. One of the enabling mechanisms, per Kaufman, is the causal chain: adverse childhood experiences arise from high entropy—or chaos—and lead to low internal and external order. Coherence decreases.

Kaufman spent considerable time on attachment (two blogs on attachment here: https://understandings.ca/2022/11/05/attachment-a-life-long-forcefield/ & https://understandings.ca/2022/11/19/attachment-as-life-long-forcefield-ii/), the source of our “internal working models” of others and self (Kaufman, 2020, p. 15, 25, 27). He did this to build a convincing argument that goes like this: poor attachment leads to weakness in the ability to form close emotional bonds. The stress from ACEs result in brain changes in five areas implicated in integration, error detection, emotional control, imagination, and vigilance. Those changes—based on our understanding of healthy development cycles— prematurely close down growth. That premature closure changes how we see people and places in such a way that we are (overly) prepared for the repetition of bad stuff. While that ain’t all bad, the fear beneath the wariness must be consciously unlearned as it is not passively forgotten.

I expected Kaufman (2020) to conclude that this leaves people with some percentage of social dysfunction, but his take is more interesting than that. He sees the deficit model as inaccurate because a different type of intelligence accrues with adversity i.e., the school of hard knocks turns out some pretty street-smart graduates. One of Kaufman’s (2020, p. 31) helpful insights is that our school systems are more geared toward scholastic smarts than street smarts. Both types have adaptive advantages which starts bringing the argument back to the safety needs at the bottom of Kaufman’s hull. He quotes Adam Grant who has stated that “getting straight A’s requires conformity” with the tacit corollary that “crooked-A’s,” the street smarties, have a huge creative capacity that often allows them to excel in different ways.

Kaufman (2020, p. 23) handles attachment deftly. On one hand he quotes Maslow stating that, “Children need strong, firm, decisive, self-respecting, and autonomous parents—or else children become frightened.” On the other hand, Kaufman wrote that “…early attachment patterns are far from destiny. So, while you and I, dear reader, might have expected safety needs to be about food, clothes, and shelter they’re actually about stability, internal environments, and meaning-driven cohesion. In essence, if I’ve got this right, one’s own narrative accounting turns out to be more determinative than the facts on the ground.

One of the most interesting coincidences of Kaufman’s (2020) work is its intersection with salutogenesis (Antonovsky, here: https://understandings.ca/2021/12/01/coherence-salutogenesis/). To quote an earlier blog:

Salutogenesis has one major premise and three ancillary premises. The major premise is that stress has to violate your sense of coherence before it can cause harm. The three ancillary premises define one’s sense of coherence:

- Comprehensibility: the conviction that life makes sense, is orderly, and predictable.

- Manageability: the belief that you have the resources to keep your life under control.

- Meaningfulness: a take on life as interesting, satisfying, and worth caring about.

We could go on, drilling deeper and deeper, but the point is to understand Kaufman (2020) on Maslow, and this is where Kaufman went: he related it to the predictive adaptive response (PAR) hypothesis (Bateson, Gluckman & Hanson, 2014). This, from the abstract: “The Predictive Adaptive Response (PAR) hypothesis refers to a form of developmental plasticity in which cues received in early life influence the development of a phenotype that is normally adapted to the environmental conditions of later life. When the predicted and actual environments differ, the mismatch between the individual’s phenotype and the conditions in which it finds itself can have adverse consequences for Darwinian fitness and, later, for health” (Bateson et al., 2014, p. 2357).

My takeaway is that coherence and hope are more fundamental to safety in the world than the physical and physiological needs cited earlier. Why? Because believing the world will hold steady, and having hope for yourself within that holding pattern, enable you to solve and conquer physiological and physical needs.

Dan Chalykoff is working toward an M.Ed. in Counselling Psychology and accreditation in Professional Addiction Studies. He works as a supervised psychotherapist at CMHA-Hamilton where his primary focus is trauma. He writes these blogs to increase (and share) his own evolving understanding of ideas. Since 2017, he has facilitated two voluntary weekly group meetings of SMART Recovery. Please email him (danchalykoff@hotmail.com) to be added to or removed from the Bcc’d emailing list.

References

Bateson, P., Gluckman, P. & Hanson, M. (2014). The biology of developmental plasticity and Predictive Adaptive Response hypothesis. The Journal of Physiology. The Physiological Society.

Kaufman, S. B. (2020). Transcend: The new science of self-actualization. TarcherPerigee Books.

Comments