Two Images

22 June 2022

There is a quiet but persistent voice inside telling me to write this blog prior to those on the role of purpose in a human life. If you’re reading this, that voice won me over.

I have always been affected by imagery. As I entered my late teens, art found a small way into my life which has continued to expand as time moves on. In the last couple weeks, the Canadian art auction house, Heffel, offered a preview of a painting now available in an online auction. I won’t be bidding but wish I were.

Last week, a friend who is a professional artist, included some sketches he had just completed, which he occasionally does in our correspondence. These sketches were different than those I have seen him complete in the last three decades. It occurred to me that juxtaposing those two images might be instructive. (At least to me.)

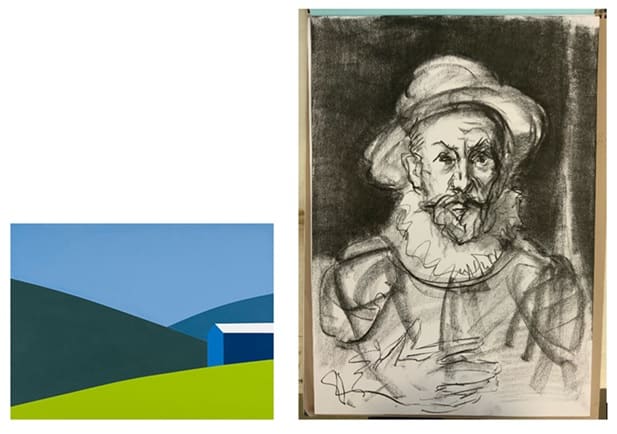

Charles Pachter, Blue Barn Green Field, David Nicholson, Don Quixote, June 2022

For the sake of easy communication, I’ll abbreviate these two images as BBGF and DQ. To begin analyzing, I think of these two images as exponents of compressed completeness and expansive suggestion, respectively. The Pachter consists of seven tones and seven planes—end of story. The Nicholson consists of gradations of light, dark, plane, and line of almost shocking variety. What is similar in both is the story telling. What is different, is the scale, colouration, and attention to detail. Yet neither is complete nor incomplete in what they suggest. And it is the incompleteness that is so fascinating.

Of some significance, in BBGF, is the parallelism of the barn roof, the top of the revealed skyline, and the baseline of the rendered field. That speaks of a rightness that values human creation as an important and apposite earthly thing—we belong here. We fit. This is us. Yet what makes the ultrasimple gable form so compelling is the counterpoint—chromatically, geometrically, and in terms of line—between the human orthogonal and the natural curvilinear sweep of hills or forests that so graciously accommodate that most fundamental of Euro-Canadian architectural forms: the barn. Finally, the proportions of the canvas are intriguing. The horizontal dimension is not so long as to make it restful, yet the vertical dimension is just short enough to make the proportion deeply satisfying. To my eye, it is a master work of understated wholeness.

To understand what I see in DQ, it is best to work from the detail, immediately above. Start with the eyes. The eye on the viewer’s right is circular and more or less eye-like. The eye on the viewer’s left is suggested with magnificently dark and loose line work. In fact, it appears that the linework overrides an earlier circle to the lower right of the eye socket. The eyebrows are so triangular as to be geometric shorthand yet both of these details, and their approximated rendering, make this an extraordinarily compelling drawing. We recognize this man, his intelligence, wariness, and dignity. Like the barn, he is archetypal, but there.

Two factors keep me glued to these works. The first has to do with speed of execution. The barn, the hills, the sky, and the field must have been painstakingly studied for exactly the most fitting proportions within the dimensions of that canvas. The relationship of the parts is magic, it works in so satisfying a manner that I could take respite in those parts, colours, and proportions for the rest of my years.

Quixote appears to have been drawn in a tempest of energy but with complete focus of intent. It is especially in that gloriously free and dark linework that I see the abandon of a hand so skilled that it trusts itself, even at 180 kilometres per hour. The suggestiveness is so convincing that the viewer sees an entire character. Or maybe, the outline is so convincing in proportion, depth, and conviction that the outline utterly convinces.

The second factor that keeps me glued to these works has to do with phenomenology. As the interpretive study of phenomena, these works have a relationship that maybe defines the earthly realm of the naked eye. What I mean is that the detailed description of Quixote is about as much character as the unaided human eye can take in while the barn is reduced to a minimized silhouette, but within sufficient proximity to see the planes of colour. Yet existentially, that is, in terms of what we know to be true of existence, seeing the barn from an airplane would reduce it further, yet each board of the barn, or blade of grass in that field, could be rendered in more detail than Nicholson has brought to Quixote.

And that’s why I see these two stirring works as well-paired—they define, aesthetically and visually, ways that people naturally see.

Dan Chalykoff is working toward an M.Ed. in Counselling Psychology and accreditation in Professional Addiction Studies. He writes these blogs to increase (and share) his own evolving understandings of ideas. Since 2017, he has facilitated two voluntary weekly group meetings of SMART Recovery. Please email him (danchalykoff@hotmail.com) to be added to or removed from the Bcc’d emailing list.

Comments