Fear of Other People’s Opinions (FOPO)

9 March 2022

In early February, I received a question from a SMART Recovery meeting attendee. I promised I would answer that question following the completion of this recent series.

I understand the distilled question as follows: Is the Fear of Other People’s Opinions (FOPO) different from a fear of loud, visible, emotional conflict? Do these fears share a common psychological origin? I believe both the short and long answers are Yes, they’re different. Here’s my understanding.

FOPO is probably genetically engrained for very good historical reasons. Anyone asking questions (or answering them) is alive today because their ancestors found a way to get along with others well enough to a) not be left behind, and b) to become part of the cooperative and voluntary network we call society. In alternate terms, it was and is a selective advantage, in the evolutionary lottery, to be a valued member of your group(s). Being left alone in enemy territory, or even in a winter march, is nearly sure death. There have been very good reasons to be a valued and cooperative member of your groups: survival. As such, I believe FOPO is about as natural as your eye colour.

In fact, as this semester finds me shoulder deep in the diagnoses of disorders, I will make a counter-wager: It is probably semi to fully pathological to have no fear of others’ opinions. I understand pathology to be the study (Greek, logos) of the origins and impacts of unwellness (Greek, pathos). If wellness requires a cooperative attitude, and I will assume readers agree that it does, the antisocial, psychotic, and avoidant tendencies, that can be fostered by anxiety, depression, and fear, can be seen to reside on a continuum.

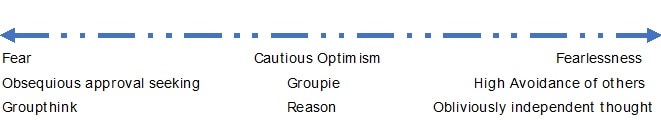

If fear sits on the left and fearlessness on the right, the middle ground is cautious optimism, which is pretty much an optimum temperament for survival. But that doesn’t cover it. If extreme seeking of approval is left and high avoidance of others right, those with tendencies toward being groupies work to ensure their survival, if not moral admiration. If recklessly independent thought is put on the right, with cowardice and groupthink on the left, where does the optimum sit? These relationships are illustrated below, Fig. 1.

Figure 1, Some of the Factors Involved in FOPO & Fear of Violent Disputes

I thought it was Socrates or Plato, but it turns out to be F. Scott Fitzgerald who provided the answer that may serve Aristotle’s moderate middle ground best.

In his 1936 essay “The Crack-Up,” Fitzgerald writes that “the test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function.” For example, he says you should “be able to see that things are hopeless and yet be determined to make them otherwise” (Sonderegger, 2018).

If a first-rate intelligence is our standard, and we buy into Fitzgerald’s test, the ability to weigh the ethics and consequences of two opposing ideas is the solution to FOPO. Well-spirited people need other well-spirited people for a dozen reasons, but the trick is identifying the well-spirited from the less so. To answer the first part of the attendee’s question, FOPO is different from a fear of loud, visible, emotional conflict, despite by belief, above.

The psychological origin of FOPO is survival within your pack—a necessity for human beings. The psychological origin of a fear of loud, visible, emotional conflict is also visceral — sewn into the neural transmissions threaded through our guts, or viscera.

I grew up with loud, visible, emotional conflicts. They weren’t fun and they weren’t productive. My recollection is that they left me and others in our home wounded, frightened, and unsure of our futures and certainly unsure of the longevity of our family unit. As a kid, without a family unit, you’re a different kind of orphan. If we think back to the last few blogs, outlining what some therapists need to know to understand their clients, Maslow’s safety needs are interesting: personal security, employment, resources, health, and property.

The safety needs were Maslow’s second from bottom tier of needs. My belief is that the fear of loud, visible, emotional conflict goes to the bottom (most fundamental) set of needs and then further up. In peaceful times, air and water are probably obtainable but not necessarily warmth, shelter, sleep, clothing, or reproductive needs. Looking above Maslow’s safety needs, loud, visible, emotional conflict also threatens our need for love and belonging which is characterized as friendship, intimacy, family, and a sense of connection (the real opposite of addiction).

As the answer emerges, the question is clearly well founded. What we see is that the fear of loud, visible, emotional conflict arises from a fear of chaos and extreme disorder that could easily be imagined ending in involuntary aloneness. As such, the similarity in origin, between fear of loud, visible, emotional conflict and FOPO, is abandonment. But with the emotional conflict, that abandonment is multi-stepped whereas FOPO can be immediate. The difference in consequence, is that belonging and connectedness are needs of well-spirited people. Chaos and entropy have the capacity to destroy, at least temporarily, everything conducive to well-spirited lives.

So where do you go with this? It smells like a boundaries issue but a difficult one to solve. As usual, it starts with one’s own self-control. As I have written before, one of the most surprising things I ever learned is that the U.S. Navy Seals tell each other, before moving into military action, that Calm is contagious.

Imagine the impact, on the loud, visible, emotional space if you sat very calmly, quietly, and peacefully just breathing to keep yourself centred. (This is not recommended if verbal or physical violence are possible or probable.) I believe this was what Martin Luther King and Gandhi began to see: placidity, or panic, spreads. Calm is contagious.

Thank you, S., for a question that turned out to be more challenging and illuminating than I foresaw.

Dan Chalykoff is working toward an M.Ed. in Counselling Psychology and accreditation in Professional Addiction Studies. He writes these blogs to increase (and share) his own evolving understandings of ideas. Since 2017, he has facilitated two voluntary weekly group meetings of SMART Recovery.

References

Sonderegger, P. (21 May 2018). Forget the Turing Test—Give AI the F. Scott Fitzgerald Test Instead. Quartz. https://qz.com/1247378/forget-the-turing-test-give-ai-the-f-scott-fitzgerald-test-instead/#:~:text=In%20his%201936%20essay%20%E2%80%9CThe,be%20determined%20to%20make%20them

Comments